How can The Milwaukee Model help develop, recruit, and retain great managers?

As a teenager, one member worked at a McDonalds under two contrasting shift managers: one was a yeller and awful, the other was caring and knowledgeable. Another realized her management ability in high school as a 4H member: she just naturally got the other kids to work together.

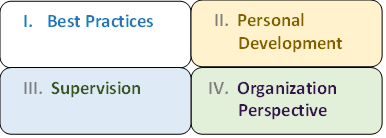

The Milwaukee Model

The Milwaukee Model is the first standard definition and model of “manager,” which makes it a ton easier to choose a career and to develop, recruit, reward, and recognize other managers. It complements the ethical and technical standards in Standards-Based Management.

3 Big Workgroup Ideas

- Sadly, most managers first learn from bad examples. Happily, they learn early.

- Their styles might vary, but all great managers have several natural characteristics

- Have a mentor at the beginning of your career, be a mentor at the end of your career

Members

Bob DeVita, Lexi Hannemann, Kristi Thiering, Michele Harris, Bill Mitchell, Bryon Johnson, Eric Nelson, Erin Lavery, Susan Dineen, Steve Johannsen, Derrick Van Mell (facilitator).

Definitions: manager and leader

5.1 Management. “A manager is someone who helps people work together.” A leader is “Someone who inspires others to take a risk.” They are not different people. At The Center, we think that good managers have good leadership ability.

What NOT to do: How did you learn to be a boss?

Valuable bad examples. All of the participants—all—said they learned how to be a boss on the job. And all of them said they learned from an early boss’s bad example. They learned what not to do, what not to say, and the high cost of making people feel unsafe.

Patchwork learning. Learning to be a boss was described as a “patchwork” process: some listen to podcasts, others read books made out of paper, some have tried online courses, a few take mini-courses.

Tangibility. Working on tangible projects (like building something) is great for developing young managers: they can literally see how parts connect, how people connect, and there are obvious milestones to mark and check progress. And they’re fun!

Good bosses don’t use people to complete projects, they use projects to develop people.

Small, Medium, Large? While a few members had first experienced management at McDonalds—and had terrible and great bosses to learn from—they did point out that McDonald’s manager training program is excellent. One member’s intern participated in Intuit’s two-year rotational development program. Clearly, it’s worthwhile investing in management ability.

Parents and sports. Some members had parents who set a great example of management and leadership, others learned from sports and remember a great coach (my high school swim coach, Greg Baker, shaped hundreds of lives). Two members had participated in Badger Boys State and Badger Girls State, which are long-standing leadership development programs in Wisconsin.

Employees and peers. All the participants valued, though often struggled to get feedback from employees—who wants to tell their boss that the boss isn’t perfect? That’s why peer interaction is so important—and that’s of course what The Center’s Workgroups are for.

Nature vs. nurture: Do managers have inherent characteristics? Yes.

Managers have wildly different styles. They can be flamboyant or introverted, creative or organized, serious or fun-loving, intuitive or logical—or some other weird mix. I had a client, the CEO of a credit union, who literally refused to touch any paper (it was his way to let you know he trusted you with the details). But whoever they are, they have innate characteristics that make them great managers.

One, empathy. They genuinely care about people. They listen, they care, they put you first. They feel—they have faith—that helping people grow is the best way to make the entire organization both successful and steadier. They can be either hands-off or hands-on, whatever’s right for that employee in that situation.

There’s a huge reward shift when you change from being a specialist to a manager. While you no longer get the immediate feedback of making something, you are rewarded by the accomplishments and happiness of others. It’s a calling, and that’s powerful.

Two, authenticity. “Let go of the role.” One Workgroup member was making the point that don’t need to act like a manager, just be the best boss you can be. Have faith in yourself.

Three, optimism—and its cousin, courage. Managers know and how to convey that, yes, you can get big things done. They know deeply that a group is capable of more than they might realize. This takes courage to make the decision and courage to persuade the executives to support the decision. They’re fighters.

Four, the drive to optimize. The member who was in 4H in high school said she learned then that she just couldn’t be inefficient. That’s probably why she’s a general manager and president today. I wonder if good bosses see a wasteful process as a waste of people’s lives.

Five, curiosity. Why do we do this? What’s the big picture? How might this thing over here connect with that thing over there? What’s the new, new thing? Good managers almost always have hobbies: one of our members is a seamstress, another is a handyman, most volunteer and serve on boards. What are you curious about?

Compassionate and competent. Great managers are also competent: They can communicate in different ways, they’re innately well organized, and they know enough about all six of the management disciplines. To understand the value of generalists, read “Range,” a book about generalists endorsed by Bill Gates.

Be the safety net. Managers make their teams be and feel safe. Without safety and trust, no one will take a risk, fulfill their potential, and make contributions meaningful to them and their organizations.

Mentors and questions: A guide on the path to self-development

Two members had the same mentor, Brooks, who not only taught them stuff, but more important, set an example of empathy, curiosity, optimism, and authenticity. All the other members fondly remembered someone who asked them good questions and provided encouragement—and perhaps most important, saw in them the potential for management.

One member had been trained and worked as a teacher, which she said was a real help. That included needing to be “in charge of the classroom.”

A mentor can spot your potential, get you started, and keep you going. The path of manager development starts with self-development (Quadrant II of The Milwaukee Model). A mentor helps you understand yourself. All these executives used personality tests and “Strength Finders.” Build from there.

No one said their MBA or other management schooling taught them how to be a manager. (Learn about getting certified in Standards-Based Management.)

How to be a “Model” Manager

The Milwaukee Model has several critical uses:

- Writing manager job descriptions

- Creating manager development and succession programs

- Aligning the organization chart with managerial job duties

- Creating objective standards from promotion to manager, executive, then CEO

Related Terms

Related posts

- New Manager 30-Day Quick Start Checklist

- The Center’s collection of “Question Craft” posts

- The value of management ability (podcast series)